In for the Long Run

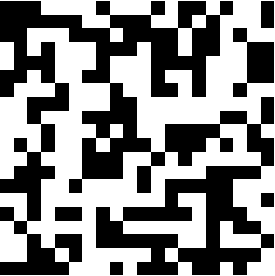

Here is a \(20\times 20\) square of bits generated uniformly at random:

Can you see any clumps? (maybe a Rorschach test is in order). Same happens in one dimension: here you have a string of 200 bits generated uniformly at random:

You’ll agree with us that the string contains a few runs.

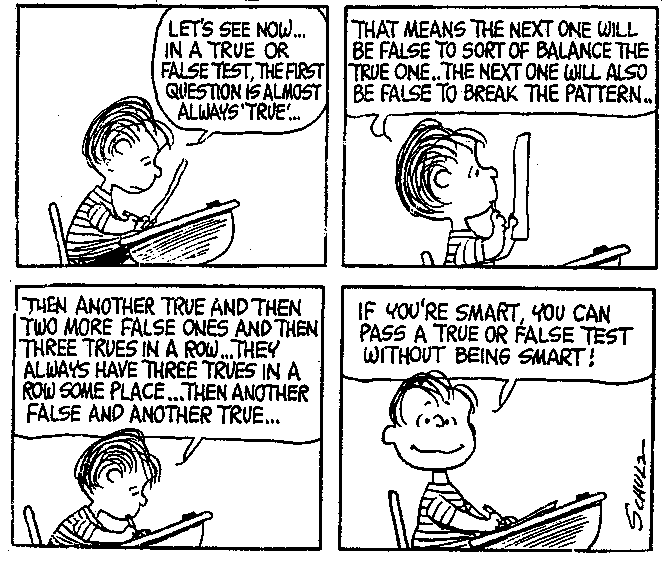

Now, Michael Jordan had 866 consecutive double-digits scoring games (is that a hot hand, or what? [1]). Björn Borg won 49 matches in a row. Joe DiMaggio had a hitting streak that lasted for 56 games [2]. We’d be forgiven for believing that this cannot possibly be random, even though everyone knows that good and bad luck come in spells. After all, even some brainy philosophers have believed that the longer the run of heads when flipping a fair coin, the more likely it is that tails will turn up on the next flip. Or maybe not.

Abraham de Moivre first investigated how to model runs back in 1718. The theory of runs got a big push in the first half of the 20th c., and an even bigger push in the second half. After a brief, naive incursion into the topic [3], we figured we’d take a deeper dive into the world of runs. We stumbled upon some exotic findings (in increasing order of weirdness):

-

• Some runs are invisible —well, you can actually see them through specially tinted glasses. We christened them null runs, but we could as well have named them ghost runs: they will doggedly haunt us and refuse to go away. A reviewer who had an early encounter with null runs was appalled enough to call them “a fringe interpretation of a run” (understandable: they are so concealed that they do not even appear in a Google search). But null runs are unfazed by human dislikes, and are here to claim a place in the theory of runs.

-

• Somewhere, somehow, there is a lonesome binary string of length \(\mathbf {-1}\) which is so dispossessed as to contain no runs whatsoever (not even null runs!). Are we starting to tread on thin ice here? We should not worry too much: as recently as the late 18th c., some mathematicians like Maseres and Frend still renounced the use of both negative and imaginary numbers [4, p. 730]. For example, Frend wrote [5, pp. x–xi]

“The first error in teaching the principles of algebra is obvious (…) Numbers are (…) divided into two sorts, positive and negative; and an attempt is made to explain the nature of negative numbers by allusions to book-debts and other arts. (…) This is all jargon, at which common sense recoils; but, from its having been once adopted, like many other figments, it finds the most strenuous supporters among those who love to take things upon trust, and hate the labour of a serious thought.”

Will our aforementioned critical reviewer’s common sense also recoil at the view of the forlorn binary string of length \(-1\)? Hopefully not, because it desperately needs more friends (and not more Frends): its only pal, the binary string of length zero (aka, the empty binary string), seems to have everyone’s full acceptance already —even if no one has ever seen it either…

-

• Strictly greater than one probabilities have pride of place in the big scheme of runs. Are we one step closer to falling into total disrepute? To try to get away with this one we’ll start by quoting Dirac [6, p. 8]:

“Negative energies and probabilities should not be considered as nonsense. They are well-defined concepts mathematically, like a negative sum of money (…)”

(Frend would surely love the last sentence…) and then Feynman [7, p. 3]:

“A probability greater than unity presents no problem different from that of negative probabilities, for it represents a negative probability that the event will not occur.”

Clear as mud? Proof by authority? Love them or hate them, greater than one probabilities are here to stay: fortunately, they only concern that shy binary string of length \(-1\), and together they make the theory of runs more aesthetic (and easier in practice).

Have we lost the run of ourselves? It might be: the whole story is in our paper [8].

Enjoy,

Félix Balado and Guénolé Silvestre

References

-

[1] A. Tversky and T. Gilovich. “The Cold Facts about the “Hot Hand” in Basketball”. In: Chance 2.1 (1989), pp. 16–21.

-

[2] M. F. Schilling. “The Surprising Predictability of Long Runs”. In: Math. Mag. 85 (2012), pp. 141–149.

-

[3] F. Balado and G. C. M. Silvestre. Runs of Ones in Binary Strings. arxiv preprint arXiv:2302.11532 [math.CO]. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.11532. Feb. 2023.

-

[4] V. Katz. A History of Mathematics. 3rd. Addison-Wesley, 2009.

-

[5] W. Frend. The principles of algebra. London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1796.

-

[6] P. A. M. Dirac. “Bakerian Lecture - The physical interpretation of quantum mechanics”. In: Procs. Royal Soc. London. A 180.980 (Mar. 1942), pp. 1–40.

-

[7] R. P. Feynman. “Negative probability”. In: Quantum implications: Essays in honor of David Bohm. Routledge, 1987, pp. 235–248.

-

[8] F. Balado and G. C. M. Silvestre. Systematic Enumeration of Fundamental Quantities Involving Runs in Binary Strings. arxiv preprint arXiv:2602.10005 [math.CO]. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.10005. Feb. 2026.

Last updated: 2026/02/11 08:32:06

[back]